Wandering the Dream Space

Sunday, 17 June 2012

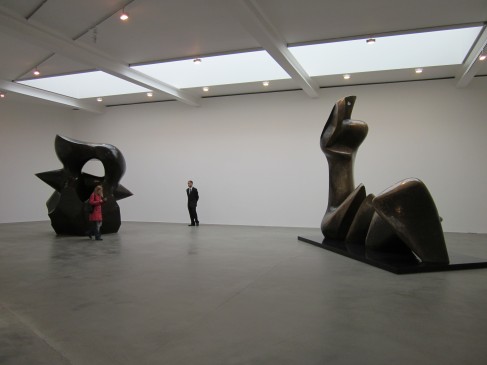

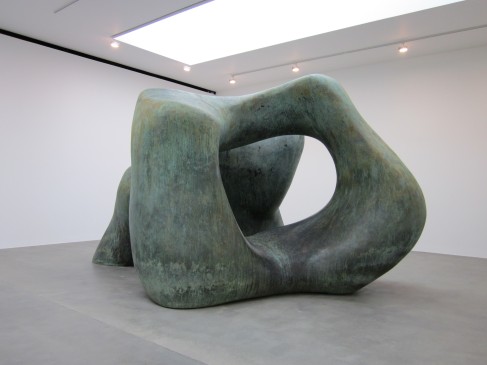

Large Late Forms

Friday, 20 January 2012

Gert & Uwe Tobias- Maureen Paley

When I get to Maureen Paley in Bethnal Green for the last day of Gert & Uwe Tobias' exhibition there is only me, and a couple with a bicycle wheel each, in the gallery. I have come to see the solo exhibition of the Transylvanian twins after seeing their woodcuts in the Saatchi Gallery's Gesamtkunstwerk exhibition.

The Tobias brothers work with a number of traditional media, almost abandoned to the folklore of artistic practice; woodcuts, typography and ceramics. But although they have honoured the luxury of all these techniques there is nothing more certain at Maureen Paley than their contemporaneity. The colours they print with are almost like nothing I have ever seen before, but remind me of the photocopy foil, Omnicrom. A typewriter is hammered at obsessively to make a typographic portrait which recalls, but is distinctly more eloquent than, a piece of computing code. Totemic ceramic creatures are enshrined in gallery corners or hanging from the ceiling.

The twins have described their work as having an 'opulence', indeed, even the dusky-dark portraits look as though they could be salvage from a water-damaged old stately home. But the opulence is really in the magnificent stretches of woodcut canvases; an opulence of labour, of colour (which does not belong to paint, but to the richer otherworldly texture of printing), of patterned gold leaf and of the fabulous creatures of imagination and myth.

The twins have described their work as having an 'opulence', indeed, even the dusky-dark portraits look as though they could be salvage from a water-damaged old stately home. But the opulence is really in the magnificent stretches of woodcut canvases; an opulence of labour, of colour (which does not belong to paint, but to the richer otherworldly texture of printing), of patterned gold leaf and of the fabulous creatures of imagination and myth.

The sense of play is important. I watch a video interview on Youtube where the cutting of the footage deliberately distorts our ability to distinguish between the identical pair. There is no sense of their individuation; one twin works on the left of the studio, the other on the right. Like conspiring children, the Tobias Twins delight in the labyrinthine twists and turns of their own game.

It may not be immediately obvious, but the Tobias twins have even manipulated the gallery space; painting the walls a rich, magnificent blue, with white lines which divide woodcuts and picture frames.

Tuesday, 17 January 2012

Daniel Kelly, Pirates of Carthage, 17th, 23rd and 24th January

This week, after almost a year of work, Daniel Kelly’s play The Pirates of Carthage will finally make it out of the studio and onto the radio waves before moving to the stage at The Nellie Dean in Soho next week.

I go to meet Daniel Kelly in his Bow Road studio in the East of London. Newly moved in, with a couple of artist friends, the space is still sparse although it has got a newly built mezzanine. Kelly is tall, he’s wearing a fuzzy Russian hat, and a slightly paint bespattered tartan jacket with a silky scarf. He looks appropriately arty, but then it’s also a ploy to keep warm. With jasmine tea, and a heater between us, we begin to chat about The Pirates of Carthage.

This is ‘A play about Tunisia, Twitter and the power of the people’. But to describe it simply as a play is a little misleading, as Kelly explains; he is primarily a visual artist and this hasn’t been about leaving all that behind to become a writer. The Pirates of Carthage would be more accurately described as a multimedia artistic project; an interactive series of performances across media, based on a collage of tweets, quotations from Gustave Flaubert’s Salammbo, Tunisian hip-hop, and a video montage of internet surveillance. On Thursday 12th January at 8pm a live interactive radio performance will be broadcast on Resonance FM (resonancefm.com/listen), on the 14th there will be a live streaming (frenchriveria1988.com, 4.30pm), and from the 16th there will be performances at the Nellie Dean in Soho.

Kelly sees his new project as having roots in his earlier practice of collaging in painting. The artistic development involved in The Pirates of Carthage, from painter to multimedia artist, was necessary in order to respond to Kelly’s inspiration; the powerful utilization of Twitter during the Tunisian uprising which led to the overthrow of the prime minister in January last year. Perhaps like many people, Kelly watched the Tunisian people revolting via Twitter in awe. Feeling the need to respond he began by taking photographs from the newspapers and working them into paintings, but this seemed too simple. He had to use the tweets at the centre of the story, and it was essential that they were read aloud. Flaubert’s Salammbo, which is included as excerpts from an audio tape, adds historical resonance to our sense of the significance of the recent uprising.

The demands of the project have forced Kelly to become a playwright, a producer, to collaborate with aDirector and actors, with Tunisians and activists, and to become a brilliant self-publicist and galvanizer of willing friends. And what kind of a manager has he been? ‘I’m usually quite a relaxed person but I have found myself getting quite stressed at rehearsals. So now, I don’t have a coffee beforehand, I’m trying to be more calm.’

There is a lot of Kelly in the project. If you go to the Nellie Dean you’ll find in the introductory visuals, the eye of the artist staring back at you. By filming his screen as he used the internet and layering this into a video montage, Kelly sifts through the accessible data of the web; BBC News, newspapers, Youtube videos of Glee asking ‘Who Run the World’?, and soft porn, until we gradually see him focusing in on the Tunisian conflict; images of Sidi Bouzid, news stories, twitter feeds. Kelly says he had to ask himself who ‘was I to be making a political work about the Tunisian conflict?’ But the video demonstrates that we all have access to this public history, and that the internet and Kelly’s play are powerful ways of understanding it.

The whole journey and artistic process has been documented on Twitter. In fact when I check on my way home a new update reads ‘Just done an interview for @flaneurzine buzzzzzzzin’ with the obligatory #pcarthage.

Kelly’s play has been devised from the archives of the Tunisian conflict’s history on Twitter, and now Kelly’s play in turn has its own digital, trackable, archive. With a kind of essential circularity Kelly pays tribute to his work’s genesis by hashtagging ‘ #sidibouzid and connecting himself back to the conception of the conflict. Of the original Tweeters; Kacem4, has created and managed the project’s blog, and a Guardian commentator will now be in the performance. This is a homage, above all, to the awe the uprising instilled in people.

If Kelly has an ambition, it is that his work can honour the original sense of collaboration and community, to prove Twitter to be as significant an artistic tool as it is political. He doesn’t believe that artists are particularly engaged with technology; they aren’t exploiting, as Kelly has, the potential of platforms such as Twitter. ‘We didn’t use the internet when I was at school’ perhaps it is only now ‘that a new generation of technologically-engaged artists is emerging.’ With a glitter in his eye, it’s exciting to think that he might be one of the first.

At the end of the Resonance FM streaming, the audience can interact by tweeting, and Kelly hopes that many of these will come from Tunisia. With any luck #pcarthage will also be trending. He likes the idea that it will be the Twitter archive, and not the book he is producing, which will survive for posterity and represent the legacy of The Pirates of Carthage. The play proves that what we so frequently see as the ‘disposable’ ‘throwaway’ comments on Twitter are actually far more concrete and lasting; ‘perhaps in years to come the internet will seem more real than any of the physical relics of our time and historians will be looking at Twitter.’

Radio Performance- 12th January, 8.00pm (GMT) 104.4fm resonancefm.com/listen

Live Stream- 14th January, 4.30pm frenchriveria1988.com

Play- 16, 17, 23 and 24 January, 7.30pm. The Nellie Dean of Soho, tickets 5 pounds (80 Dean Street, W1D 3SU)

Artist Talk- 21 January, 7.00pm

ticket booking: frenchriviera1988.com

pcarthage@gmail.com

piratesofcarthage.wordpress.comfacebook.com/pcarthage

Monday, 2 January 2012

The Peripatetic School: Itinerant drawing from Latin America

Tony Cruz, Distance Drawing San Juan/ London, an attempt to draw the distance from San Juan to London (6,751.2362m). Realised only 0.0031890 percent (2,153m) 2011, Dibujo Distancia

Tony Cruz, Distance Drawing San Juan/ London, an attempt to draw the distance from San Juan to London (6,751.2362m). Realised only 0.0031890 percent (2,153m) 2011, Dibujo Distancia Mateo Lopez, Nowhere Man 2011, Mixed Media Installation

Mateo Lopez, Nowhere Man 2011, Mixed Media Installation'Drawing has always been the most portable medium' claims the exhibition blurb. Tony Cruz's Distance Drawing, a pencil drawing made directly onto the wall of the old factory, is like the automatic scribblings of a seismograph. It feels like the obsessive scribblings of an artist desperate to record; and yet its obvious portability destroys the illusion. How many times will the unfinished drawing be reproduced, and how is it transported between galleries, from wall to wall?

The installations of Mateo Lopez and Ishmael Randall Weeks look as though they could be packed up and carried away. Lopez's Nowhere Man is a temporary home with desk drawers filled with maps, and more suggestive materials scattered about than can be processed in a single viewing. But the overall sense is of its emptiness. Randall Weeks' Fragments is my pick of the whole exhibition; an architect's table of sketches and plans, towards a Utopia? But once again it has been abandoned, stranded in Bermondsey.

Friday, 23 December 2011

A Poetry of Light

The year has ended with a confessional of denouncers of video-art; Charles Saatchi dismissed it in his attack on the art world, and Waldemar Januszczak added 'please no more video art' to his Christmas wishlist, using Dean's giant film as the most irksome example of all.

And yet for me Dean's film is a beautiful tribute to a passion for her medium. Pure visual luxury. A poetry of light. A series of hypnotic images spliced together, saturating and shifting through filters. Uniquely accessible above all, not elaborately conceptualised or filled with the cold intellectualism which makes video art only briefly bearable. There is only a soft murmur above the film's visual soundtrack and tones of silence. The delicious hush of a captive audience.

In the Turbine Hall, dark except for the warm, drowsy luxuriance of Dean's video, there is something of the cinema. People sit on the floor in perfect silhouettes. Children totter up to the screen only to be shooed away again. The best manifestations of the Turbine commission are about interaction, have the power to transform the vacuous space into theatre and theme park.

It has the melancholy of obituary about it; Dean is painfully aware that her medium is dying even as she celebrates its richest qualities. Yet there is a joyous buoyance too; growth and regeneration, giant balls float gently in the Turbine Hall. The Turbine Hall projected onto the Turbine Hall, seems like a generous thank you to the commission itself.

Waldemar ends his Christmas wish list by requesting that at least, there will be a time limit imposed upon video art of 2 minutes maximum. But I sit on the cold floor letting Dean's visual poetry wash over me like the cascades of the waterfall in the film. I could give all my time to its entrancing assault on my senses. For me Dean's films is one of those legendary Turbine commissions, like Ai Weiwei's sunflower seeds or Carsten Holler's slide, that I will always be able to say that I saw. It is a lyrical affirmation of the importance of video art in a year of dissent.

Sunday, 6 November 2011

Treasure

'For surely they are not only lovely pictures of fragments of a lovely creation, they are patterns of things we all know if we have ever really lived: they are Figures of the True.'

'one never knows where a book may wander'

Wednesday, 10 August 2011

Ascension

We arrived in the church of San Giorgio Maggiore as a man and a woman emerged from a trap-door in a grey painted platform beneath the Dome. We took our seats in anticipation as four walls of fans whirred to an exhausted stop and left only an eery silence. We had arrived at Anish Kapoor's Ascension at the beginning of its lunch break. On the Venetian island of San Giorgio there was plenty Biennale to keep us entertained while we waited for Kapoor's installation to siesta: a photography exhibition of Real Venice, an exhibition of developments in tapestries, Penelope's Labour.

At 2.30 there were crowds of people on the white-hot stairs of the Abbazia waiting for the doors to open on Kapoor's miracle. Even if you see the mechanics exposed; the invigilator disappearing to switch on, the fans warming up and Kapoor's ghost struggling towards ascension; the installation retains the quality of miracle. Smoke or mist,spirit or ghost; Anish Kapoor has created the perfect illusion. Installed here in the dome of

San Giorgio's beautiful church it takes the viewer's breath away. A twist of dusty air curls up towards the heavenward cupola; a spirit ascending to the highest heights of religious experience.